Here’s the short answer, unless you are on your own boat, understand and are willing to take the risk, don’t do it. If you are interested in why, read on.

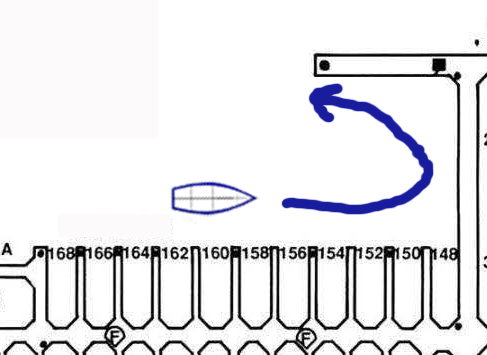

When sailing on any point of sail from a close haul to a broad reach, a jib is not nearly as effective as the main. A large part of the reason why boils down to something called the Center of Effort (COE) vs. the Center of Lateral Resistance (CLR). Without getting too technical, COE is the specific point in the sail plan where the force of the wind trying to move the boat forward is focused. Each sail has it’s own COE, located more or less at the geometric center of the sail. The boat as a whole has a COE located between the COE of the jib and the COE of the main. There are a number of factors that can influence and move the COE forward and aft. Factors that are expanded upon in the Advanced Coastal Cruising class, so I won’t go into them here. For now, as I indicated, a simplified version says the overall COE should be located somewhere between the jib COE and the main COE.

CLR on the other hand is below the waterline. It is the point where the boat is perfectly balanced fore and aft. Push on that point, and the boat will move directly away. Push forward of the CLR and the bow moves more than the stern. Push aft of the CLR and the stern moves away.

The net result is that while sailing, the COE should be above and slightly aft of the CLR. Doing so results in a slight amount of weather helm (the tendency of the boat to want to turn towards the wind). If you remove the main from the equation the weather helm goes away and is replaced by lee helm because the COE is now forward of the CLR There are several down sides to lee helm. First, you loose the feedback at the helm that weather helm gives you. Second, it is very difficult to head up with lee helm, and even more difficult to tack. Typically, the boat will stall half way through the tack, ending up in irons. Finally, an untended rudder on a boat with weather helm will turn into the wind and stop. With lee helm, the boat turns away from the wind and continues to run until something (like a lee shore) brings it to a stop. Yeah, I know, how many sailors are going to walk away from the helm and let that happen. You may not have a choice. Maybe you just fell overboard, or even more likely, the steering breaks, and you no longer have control of the rudder. It happens, far too often for me to want to take a chance.

That brings us to the one situation where sailing under jib MAY be OK, sailing downwind in a mild to moderate wind. However, there are a number of caveats. First, make sure you have a backstay! Several years ago, three boats in the Caribbean experienced rig failures, on the same day. The problem, no backstay to absorb the forces placed on the mast. The wind was above “moderate” resulting in the masts falling forward. In this case, all three boats were Hunter’s, however, any boat with no backstay is subject to the same problem. Also, if the forestay is fractional (does not go all the way to the top of the mast) then the forestay and backstay don’t match up. The forestay attaches a number of feet lower, placing uneven pressure on the mast. When the main is up, the leach of the main helps ease that pressure.

Basically, we have now eliminated nearly all situations. To recap:

- Don’t sail under jib alone close hauled, close reaching, or beam reaching.

- Probably not even a good idea to sail under jib alone on a broad reach.

- Don’t do it on a boat with no backstay

- Fractional rigs can be a problem.

- A jib alone in anything more than about 15 knots is asking for trouble, for example, furling it will be a challenge, the mast can “pump”, and your bow is going to tend to be forced down (not a good idea when surfing down a wave face.)

- And, finally, think about what happens if you loose steering control. With a main, you can bring the boat into the wind and stop while you deploy an anchor. With a main and jib, you can actually steer the boat by either trimming the main and easing the jib (to head up) or trimming the jib and easing the main (to bear away).

All in all, sailing under jib alone is not a good idea. If you are sailing your own boat, and you understand the risks (all those items listed above), then go for it, it’s your boat. If it’s not your boat (aka a Tradewinds Charter) there are too many things that can go wrong, all of which may result in painful injuries to you, your crew, or your pocket book.