A few weeks ago I had the opportunity to watch one of the Tradewinds boats from a distance “struggling” in 25 knot plus winds at the eastern entrance to Raccoon Straight. My initial thought was that the boat was in trouble, so we started in that direction to lend assistance. As we got closer, we realized the motor was running, the boat was head to wind, and the crew as struggling to get a reef in. It wasn’t fun to watch. Both sails were being trashed by the wind (we needed to restitch the jib UV cover the next day) and the resulting reef was very poorly set. Watching it reminded me of one of my mentors as I was learning to sail who had a favorite saying … “If you can’t reef under sail, San Francisco Bay will eat your lunch, and you have no business sailing there!”

As an instructor teaching Bareboat and Advanced Coastal Cruising classes, I have come to realize the truth and wisdom in this statement, and sadly, how may sailors out there can’t do it when it is actually safer, easier, and much less noisy than turning on the motor and pulling up head to wind.

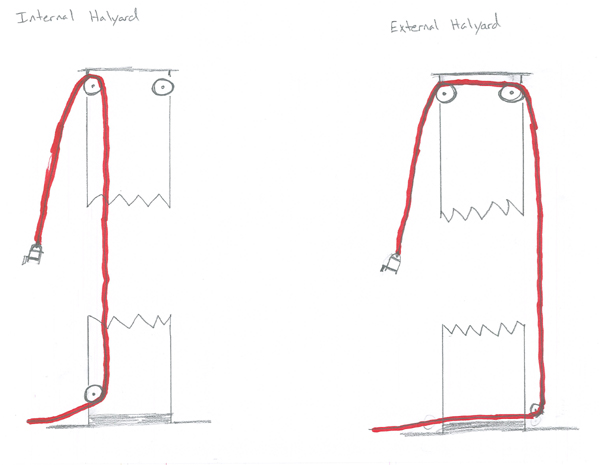

To put a reef in under sail, come close hauled, trim the jib, and release the main. While the main is released, the boat will heal less allowing you to comfortably ease the halyard and put in the reef. Typically the reef tack is set first, followed by the reef outhaul, and then the halyard is adjusted. It is truly as simple as that. The only challenge is understanding the exact process as it applies to different boats. Some boats have two lines (tack and outhaul) for each reef. Some have a single line that sets both tack and outhaul. Some have a hook and ring at the tack. Some boats are so simple as to have a roller furling main that just needs to be rolled up a bit. Regardless of the set up, sail close hauled with the main released and reefing will be a snap.

What happens if you are sailing short handed and your crew is scared and not able to help. It’s not quite as quick and efficient, however, try reefing while hove to. Generally that can be accomplished without the help of an untrained crew member.

One final thought. Remember the rules of the road. Reef while on a starboard tack and you will generally be the stand on vessel.

Anchor?

Anchor?