If you have been certified through Basic Coastal Cruising, you will have learned how to properly connect mooring lines to the buoys at Ayala Cove, named after Juan Manuel de Ayala y Aranza, the first captain ever to sail into San Francisco Bay. But our favorite Cove has been shoaling up just like the rest of the Bay since sea levels rose when the great ice sheets retreated 10,000 years ago. Now I’m not quite that old, but old enough so that observable geological changes have taken place during my tenure. Years ago, when I first hiked out to Arch Rock at the end of the Bear Valley Trail in the Point Reyes Seashore, there was a massive rock arch there, and there was no problem with the depths at Ayala Cove. Now the arch is gone, and we have to pay attention to the tides when visiting Angel Island. I’ve changed a bit myself.

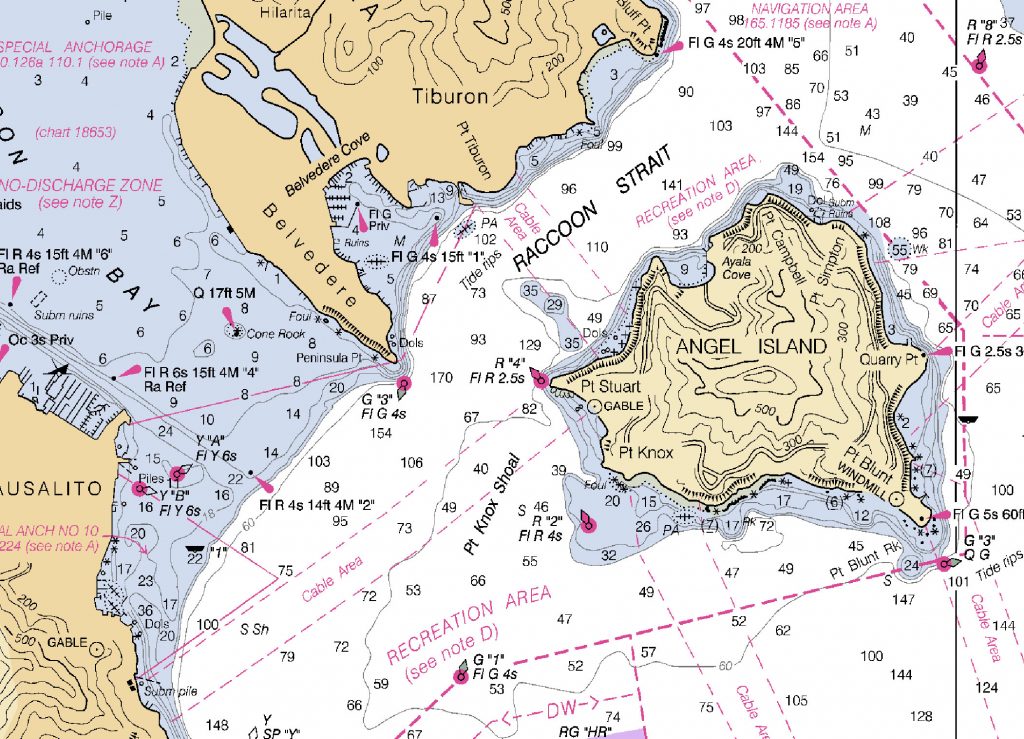

San Francisco Bay is an estuary at the end of the Sacramento River, which carries sediment all the way from the Sierra. As a matter of fact, the sediment is the Sierra. Some of that sediment makes it out the Gate and creates the Four Fathom Bank, but a huge amount is left on the floor of the Bay. If you look at Raccoon Strait on the chart, you’ll see it is very deep, and that is because until the end of the last ice age, when the ice melted and sea level rose over 300 feet, it was a ravine that carried the Sacramento out through the Golden Gate and 25 miles west to the coast, the ancient shore of the Pacific Ocean. This ravine, now filled with water, continues to be scoured by every ebb and flood as does the Golden Gate, and for this reason they have not silted up.

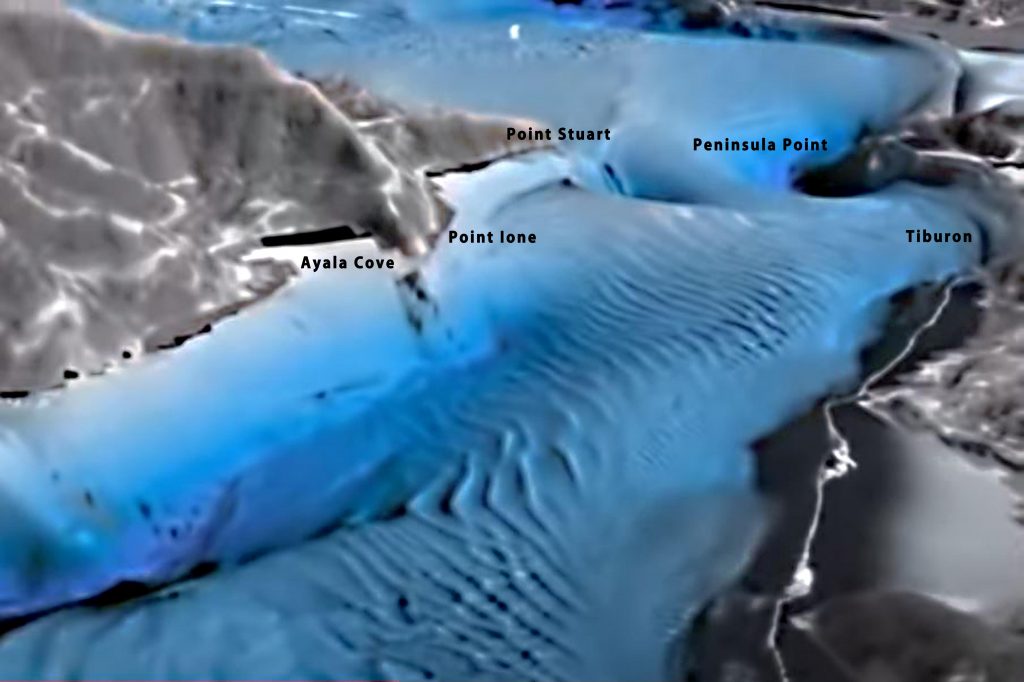

Below is a bathymetric image of the topography of the bottom of Raccoon Strait looking towards the Golden Gate. Notice: 1) How deep the Strait is relative to Ayala Cove. The fact that it is a cove, or indentation in the hills, has meant that over the centuries, it created an eddy where water slowed and dropped its sediment, resulting in a beach. As the ocean rose following the melting of the glaciers, the beach rose with it. The same is true of Keil Cove across from Ayala Cove, the bight between Point Ione and Point Stuart, Richardson Bay, and Belvedere Cove. If the water were to be drained from the Strait, the areas in light blue on the nautical chart above would be flat ledges next to a steep, daunting cliff descending to a cavernous gorge. This sedimentation process continues today, which is why we need to be vigilant when sailing there. 2) The big hump on the bottom just westward of Ayala Cove and opposite Tiburon creates the riffles in the water that you will always encounter there in a strong current, as the rapidly flowing water rises to clear it. 3) The deep holes off of Point Stuart and Peninsula Point are caused by the flow of the current rushing around the points through this constriction, just like the rapids on a river. In a strong current, you will notice turbulence near both the western and eastern approaches to the strait.

Together, these features dramatically illustrate the power of water to shape land. They also reveal an entirely different sense of the roiling flow that lies hidden below the two-dimensional current that we see on the surface. Our marine mammal friends spend their time in this very different world. Similar sculpting takes place anywhere there’s a strong current meeting a constriction or obstruction, like around Alcatraz and of course through the Gate. It’s a ghostly, powerful world down there.

Back to the practical matter of shoaling at Ayala Cove: If you are staying overnight and the boat settles on the bottom in the evening, it won’t hurt the boat, although it may spill your tea as the boat heels. But you’ll have to plan your arrival and departure so that you can get in and out. Of course, you can look the tides up online, using the tidal corrections for either Angel Island (west side), or Angel Island, East Garrison. This will show you a beautiful sine wave. But suppose you don’t have an Internet connection. Here’s a method to figure the slope of the rise and fall of the tide for Ayala Cove, which will also be of service at Sam’s, Clipper Cove, Richardson Bay, and any time and anywhere you have only a tide book:

1. Find the tides at the Golden Gate in your book.

2. Apply the correction for Angel Island (west side), which will work for Ayala Cove:

Time High water +13; Low water +21

Height High water -0.2; Low water 0.0

3. Use the Rule of Twelfths in the paragraph below. This is a way to create a sine curve for the rise and fall of the tide without having a graphing calculator. It allows you to interpolate between the high and low tide to determine when there is enough water for your boat to enter without grounding.

There are about six hours between low and high tide. Divide the total difference in height between them by 12. In the first hour the height increases by 1/12. Then in the second hour by 2/12, in the third by 3/12, in the fourth by 3/12, fifth by 2/12, and the sixth hour, 1/12. These together will add up to the tidal difference. To go from high to low, do the same thing in reverse, subtracting instead of adding.

Just put that steep cliff, close by out towards the Strait, out of your mind.

Great, informative article. And those of you (us) who left basic math skills in high school. Here is a calculator for rule of 12th.

https://planetcalc.com/2450/

Very cool. I didn’t find an app for that after a brief search, but there ought to be one.

You should write a book… !!!