There is really no such thing as safe to go; if you want to be safe, don’t go. Said Saint Thomas Aquinas seven centuries ago: “If the highest aim of a captain were to preserve his ship, he would keep it in port forever.” Actually, even that won’t work. And that’s not why we build ships.

Now, of course there are easy sails, many blissfully so. The problem is that in advance, you just don’t know which ones they are. I’ve gotten into terrifying trouble right at Point Potrero, or next to my mooring in Tomales Bay, saved by what I like to flatter myself is seamanship, but equally credited to a benign nod from Poseidon. You’ve chosen to be a sailor, and that means that although safety is a priority, you don’t choose to be safe and comfortable at the expense of a mundane and prosaic existence. You’re willing to take some calculated risks for the sake of adventure and challenge. But if you’re going to seek adventure, it’s a good idea to bring your brain along, just in case.

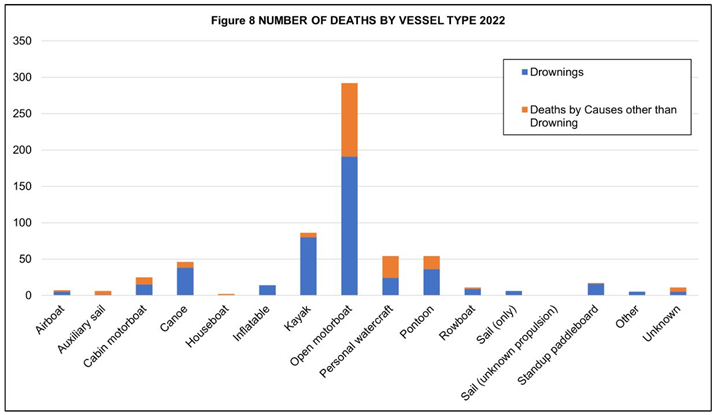

Compared many things we do all the time, sailing is quite safe. You’re many times more likely to have a serious accident driving to the marina than on the boat. And among various types of boating, sailing is among least risky. According to the Coast Guard, canoes are more dangerous:

Nevertheless, the prudent mariner takes nothing for granted with regard to safety. Now I’m not superstitious and do not adhere to the precautions of sailors of yesteryear, like prohibiting bananas or never leaving on a Friday. But still. When I get ready to untie the lines I’m reminded of the great Jerry Rice, who dressed meticulously before entering a football field to do battle and get muddy. If I’m about to go face the sea, an adversary much more formidable than some mere flesh-and-blood competitor, I’m gonna get myself ready.

The best way to be a safe skipper is a bit of a catch-22. You do it by sailing. The more you sail, the better you will be able to manage the boat without becoming overwhelmed when things go all ahoo. Spending time with every seemingly minor detail you are taught by Tradewinds contributes to your being safe to go.

More specifically, Tradewinds requires completing a checklist prior to departure represented by our acronym, “safe to go.” But if you charter elsewhere, you may not have such a list to jog your memory, and that’s when having memorized “safe to go” comes in handy. Many of these are mechanical items, often checked off perfunctorily. But is the skipper safe to go? Does he or she understand how to use all these things quickly in an emergency? Of all the gear on board, nothing is as important to the safety of the boat and crew as the mind of the captain. It’s also the most likely to malfunction.

……………………

S is for safety gear. In over 40,000 miles, I have used few of these; but I’m certainly glad I had them aboard. As Brandy’s dad Butch, a great sailor, is fond of saying in a phrase worthy of Captain Ron, “It’s not a problem until it’s a problem.”

We are required by the Coast Guard to have certain gear. In addition to those sensible items, the competent skipper will check the boarding ladder, first aid kit, wooden plugs, radio, anchor, boat hook, extra lines, charts and the tools to use them, and compass. It is not sufficient to merely check a piece of gear off the list. You need to be able to clearly explain it to your crew when things get dodgy and your mind is flopping around like a wounded snake. Panic in the face of the skipper is not a look that inspires confidence. Two examples of things you should inspect, in case their deployment is not as obvious as you may assume, are the main anchor and the emergency tiller, so be sure to familiarize yourself with these. When things go pear-shaped, these will have to be deployed without hesitation. That is not the time to be figuring out how they work.

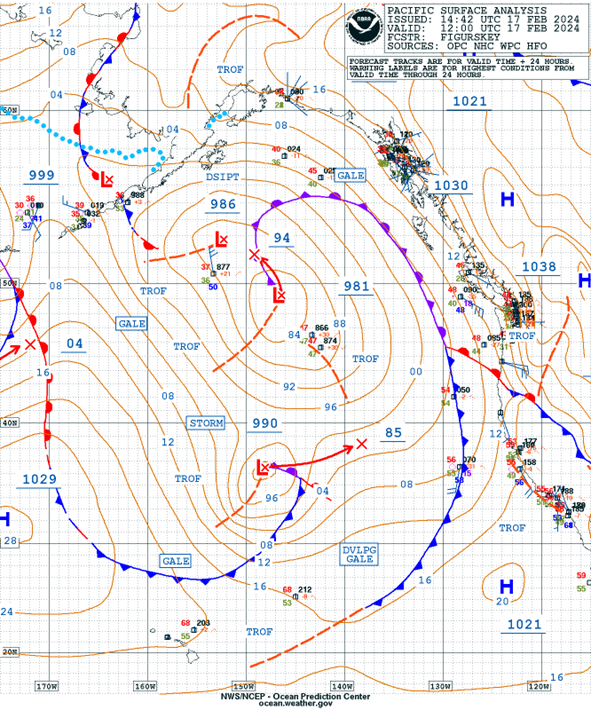

A is for atmosphere. In San Francisco Bay we have two major weather patterns, summer and winter. Fall and Spring are a mix of the two. It’s easy enough to check the weather for any given day, but knowing the reasons behind the weather in the forecast may help visualize what is happening and respond to predictions. This can be confusing with regard to a small craft advisory. In the summer, our prevailing wind in the Bay is caused by the heating of the Central Valley, which creates a thermal low when hot air rises after the ground heats up in the afternoon. This sucks air through the Golden Gate, the only gap from the ocean through the coastal mountains, and into “the slot,” and when this is strong it triggers a small craft advisory. In the summer, while the breeze at the city front may be in the mid-twenties, you may see only ten knots in the Oakland Estuary which is hidden from the venturi around the Golden Gate. The great thing about this is that in the summer, you can pick your conditions. Not so in winter, when the Central Valley doesn’t get hot. The weather we see will be part of the larger, synoptic pattern, so the results are not so easily managed. In the map below you see a front extending from Alaska to Mexico, which will bring wind and rain to the entire Bay as it heads east. There will be no escaping to Oakland; the small craft advisory will pertain to the entire area.

If you charter abroad, your charter company will almost certainly help you with local weather.

If you cruise privately, however, you’re left to your own devices. You should learn how to read a weather chart like the one below. If you have Starlink, these can be viewed online but if you don’t, there are other ways to do it. You may have to rely on local VHF weather, which may be in a foreign language. You’ll have to do some homework on your alternatives in each area.

F is for floorboards. This means checking automatic and manual bilge pumps, and locating each thru-hull valve so that you can find them in the dark. I don’t wish to alarm you, or maybe I do, but if one of these is left open and the hose somehow fails, you need to check them all immediately. If enough time has passed so that there is water in the boat submerging the valves, you won’t be able to see them and it will take too much time to try to figure out all the locations by looking at the manual. You need to have a map of them in your mind before you leave the slip. All but the valves for engine cooling, and for the packing gland if fitted, should be closed when underway and not in use.

E is for engine and here I also include electrical. Do your engine checks, safely disconnect shore power, and make sure the VHF is on and set on channel 16. A cautious skipper will inform his crew, briefly, how to use the radio in an emergency in case the captain is injured or occupied. Nowadays, the Coast Guard may ask for a mobile number to continue a call. This gives you the advantage of being able to move around the boat and attend to things instead of being stuck by the VHF.

T is for tides and currents. Know how to use the tide book to adjust tide time and height for Richmond, or for where you plan to sail, particularly if this is to shallow Richardson Bay, Ayala Cove, or Clipper Cove. Adjustments are found at the beginning of the tide book, on pp. 11-13 in the current edition. For currents, check pp. 50 and following for min-charts of the bay. These show, graphically, the flow of the current for every hour during the tidal cycle. You need to be familiar with using a tide book, even if the app on your phone is your preferred method. The way our book works is the same way they work in French Polynesia and the Mediterranean. If you have no Internet, the book is your fail-safe.

O is for on-deck rigging. Make sure you know which lines are which, particularly the reefing arrangement. At least one person besides the helmsman will be required for this procedure, so make sure your crew understands the lines, and that you understand them well enough to describe the procedure step-by-step to crew if you need to stay at the helm.

G Check the fuel level.

O Check the steering, and find the emergency tiller. Don’t just locate it; install it. They are all a bit different and some are counter-intuitive. On Papagayo, for example, the tiller is reversed, so you’ll have to steer backwards from what you’re used to. Try to avoid putting yourself in a situation where you have to back up the boat using this arrangement, as with a truncated tiller you won’t have the necessary leverage to control the rudder.

Being safe to go isn’t just about mechanically checking off these boxes. It is centered in the knowledge of the skipper, who is satisfied that all the necessary preparations to keep the boat and crew safe have been attended to. The confidence that results will be clear to guests, and will give more comfort to those unfamiliar with boats. The lack of confidence that comes from a hasty and ill-planned departure will also be recognized by them. They will not be put at ease by it.