After 40,000 sea miles including a circumnavigation, some might picture me as an old salt who loves the sea. It’s a good guess, as I’m for sure old. But I have little affection for the sea. One wants one’s love to be, if not reciprocal, at least directed towards something that is not a bipolar psychopath. On some days, the sea is just lovely, while on others, it may run you down and leave you maimed or dead without so much as a backward glance. A shooting star is pretty too—until it lands on you—and just like that asteroid, the next gale might have your number. To give credit where it is due, the sea is an egalitarian destroyer, granting no preferential treatment due to your age, experience, race, gender, skill, country of origin, net worth, or affability. You have to admire that level of even-handedness.

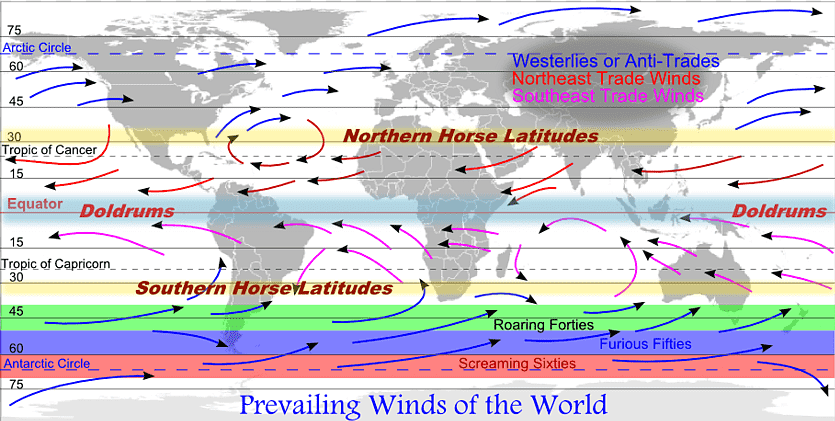

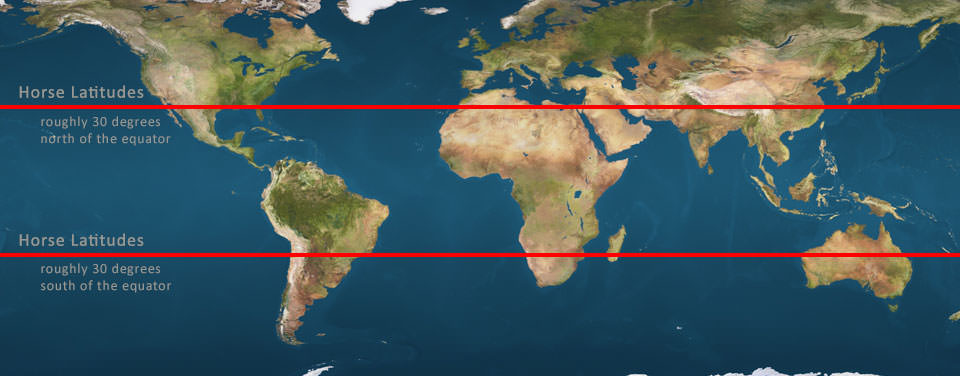

The sea is also a bit of a creepy place, an environment our landsman’s evolution never prepared us for. On my first ocean passage, to Hawaii on Ted Stuart’s September Song, we were becalmed in the Pacific High and decided to take a swim. Everyone was having fun diving right in, but when I followed, I was immediately filled with a horror I could never have anticipated. I got back on the boat as fast as I could, and have never been in the ocean offshore again. Call me a silly coward, I’ve heard worse. At the beach, the water’s fine of course, but then, land is close by. Out there it’s around three miles down, incomprehensibly far away, and when you stare out underwater you don’t know whether you are seeing a hundred yards or three feet. I felt a visceral unease in its vastness. To make things worse, there are critters in that water that the most creative science fiction writer could never have imagined. Some are graceful, transparent fantasies that perform intricate light shows. Then there are those that are the stuff of nightmares. It’s more unexplored than the surface of the moon, and according to the National Ocean Service, 91 percent of the creatures living in the ocean have not yet been identified. Considering the strangeness of what we do know, that plays on the mind. There are animals who live contentedly where no light can reach, in pressure that would squash you to the size of a pea. Some have weird senses that enable them to perceive things you are blind to. This environment is where these alien beings are at home. What could they be thinking? Even now, it gives me shivers.

Yet I am fond of being at sea, the farther from shore the better. Close in, your reveries must be interrupted by concerns about mundane issues, like hitting ships or land. Offshore, being at sea is gratifying on many levels, even putting aside the spectacular sunsets, sparkling clear starry nights, and infinite vistas of blue sky and thunderheads a hundred miles away. Out there, I am continuously reminded that every mile we travel is accomplished on the shoulders of the first sailors, giants lost to history. To these phantoms from ages past, we owe our ability to survive in this unfamiliar world where we were never meant to be. They went there first. I feel a fellowship with them, a bond, and immense gratitude for having been the beneficiary of their collective daring, perseverance, canniness, toil, and suffering. What a wild imagination our ancient forebears had, to sail out where there might be dragons! What recklessness!

Go to a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. You can picture yourself kayaking fifty yards from shore, but farther out, the horizon is something altogether different, the portal to a deep mystery. Now imagine that you’d never heard of anyone that had tried to get out there, or if they had, they were never seen again. This was the situation of the very first Polynesians. What gave them the audacity to reckon that unlike the others, they could travel beyond that line into the spooky unknown, beyond any hope of contacting the people who were dear to them, and survive?

It is a deep honor to sail in their wake.