What is it like to go from being a novice sailor, to navigating Tradewinds classes, and then ending up a boat owner? Well, exhilarating, fun, serious, not without some expense, and a few unanticipated outcomes. This is my journey from dreaming about sailing to, as I sit here in my 1986 Pearson 36.2 writing this article, becoming a boat owner. Tradewinds got me here and then I could go to aceboater.com to get fully licensed to drive a boat. It’s cadre of instructors gave me the skills, knowledge and inspiration that set the heading.

It was 2008 and I was coming up on

retirement. I was attending a motivational workshop along with work colleagues.

When confronted with the question about what gives my life meaning and to what

future action I could commit, I impulsively blurted out that I would learn to

sail.

That bold projection was not entirely out of character for me. I’d been physically active all my life, mostly with mountaineering pursuits, and the thought of sailing a good size boat truly inspired me. If you are looking for a small boat, I recommend the 1970s Sears 12ft fiberglass jon boat for sale. The right boat accessories and marine engine mounts should also be chosen carefully. You may also be needing replacement for some diesel engine parts like this in stock Roosamaster pumps here.

But how to do it? As I started checking out the various San Francisco Bay sailing schools, Tradewinds—with its range of opportunities and costs—kept popping up. Then, a friend of similar age and interests, having just finished the Club’s Basic Keelboat class, invited me to join him on one of the Capri 22’s. That did it. I was all in.

Sailing fit me. While most people gain their perception of sailing from magazine covers featuring turquoise waters and bikini clad 20-somethings, I was influenced by the historic rigor of the sport, the mental and physical challenge posed. As a history lover, I was fascinated by the early sailing skills of the Pacific Islanders, the Arabs who sailed the Mediterranean and beyond, and later the indomitable global courage of the European explorers of the 15th to18th centuries. The historical combination of emerging nautical knowledge, the tenacity, and yes, even the hardships, provided a motivational model for me. Imagine those early years sailing thousands of miles from a safe port to points unknown. Since the science hadn’t evolved, the destination and the precise route were impossible to calculate. Fearlessness and audacity prevailed. If you want to buy a sailboat one day, you can try gaining some cash by simply playing games like 배팅노하우.

A stroke of good luck accompanied my journey. While the wives of most male sailors are less enthused about the sport, ranging from indifference to downright resentment, my wife, Kathleen, agreed to take classes and eventually took Tradewinds’ Basic Keelboat through Bareboat Chartering. Little did we realize within a few years we’d need her skills. Out of this, she too got hooked. I recall two moments that solidified her love of the sport. The first was an America’s Cup Race day. We were sailing the Club boat, Satorini, just the two of us, when the race was canceled because of high winds. Reefed, sailing comfortably, we continued throughout the day. That gave her confidence. The second moment was the last day of our Coastal Cruising class. We were docked in Sausalito to take the final exam. Questions ranging from the inner life of diesel engines to navigation, distinguishing radar images, and route planning were formidable. Kathleen took one look at the questions and laughed. Literally. There was no way she could pass this test, she thought. She nearly aced it. 95%.

Learning to sail was not without its,

well, adventures. I can still remember the day we were out on one of the

Capris. The wind died, we started drifting dangerously close to the Chevron

pier, and I couldn’t get the outboard started. I pulled that starter cord again

and again. At the point where we were about 30 feet from the pier, I called the

Tradewinds emergency number and got Butch. Calm as could be he said, “Close

that choke, open the throttle all the way and pull the starter.” We were back

safely in Marina Bay within 30 minutes.

I increased my sailing skills with other

Tradewinds’ classes— Advance Anchoring, Docking, Radar, and others. Expanding

my membership and moving up in boat size and complexity increased my knowledge

of the relative easy or difficulty of each type of sailboat. At anywhere near

15 knots one boat had to be reefed, while another with full sails handled fine

in similar conditions. I started thinking furtively about someday owning a

boat, wondering about what features I’d want, while at the same time

admonishing myself for such luxurious fantasies. Might there ever be a day?

Kathleen and I started Bare Boat

Chartering—first to St. Vincent and the Grenadines, then to the Bahamas. Is

there a nicer place to sail than the Bahamas? I don’t think so. Meeting other

sailors and boat owners at Tradewinds resulted in invitations to sail in the

Sea of Cortez and throughout the Caribbean. Family members accompanied us on a

Bare Boat trip to the San Juan’s.

Then, suddenly, opportunity appeared. I

owned a second home which had been financially underwater for several years.

When the market came back and the house appreciated, I saw my chance. My wife

was completely supportive. This is an area that can cause relationship

difficulties. Typically, (though not always) it’s the guy’s dream and the wife

is usually, at best, only lukewarm to sailing. I’m a lucky guy. Proceeds from

the house sale gave me a modest pot from which to start looking for a boat.

You might think the San Francisco Bay Area would offer an incredible range of used boats for sale. Well, yes and no. I set a firm price limit and placed aside a chunk of money to do the unavoidable repairs that come with an older boat. Two principles guided my search. I wanted the highest quality boat and for the price not to exceed the dollar amount I imposed on myself. Casting my net far and wide, I even began to look into every viable boat dealer in Florida where boats often sell for less. A sailing friend in Los Angeles checked out a boat and, with his recommendation, I actually scheduled a survey. Then, two days before I was set to fly to L.A. for that survey, the Pearson came available here in Sausalito.

By that point I had done a desktop review of scores of center console boats and had personally viewed 8 to 10 that seemed possible. The Pearson was owned by a Bay Marine Pilot who had taken meticulous care of it. I called Matt at Tradewinds for a referral of a good marine surveyor. And between the evaluations of friends and the surveyor, the boat came out a winner. Pearsons, I started to understand, had a great reputation, far exceeding more popular models on the West Coast. Built in Rhode Island, it’s uncommon to see one in California marinas. The fact that the standing rigging had been replaced one year earlier, there was only about a 1000 hours on the engine, a maintenance log showed frequent attention, and the boat had a fairly new jib were just a few facts that convinced me of its value.

Yes, the inevitable repairs of an older

boat started soon after I bought it. Within four months, the main sail had to

be replaced. That was three boat-bucks. Later that year, the engine exhaust

stopped expelling water and the mixing elbow had to be renewed. Yet, wisely, I

had held back funds for these repairs. That made the pain tolerable.

So, why buy a boat when Tradewinds

membership is such a good deal? Each individual has to answer that him/herself.

I was fortunate to have the cash from selling my second home. Otherwise, I’m

afraid taking out a loan would have disrupted the domestic harmony necessary in

balancing family finances with boat ownership. It’s a financial commitment, no

doubt. The ongoing expenses easily exceed the Club’s membership fees. Yet, the

romance of a sailboat crept into my heart. My boat is, as I call it, my

sovereign nation, and I rest with the fantasy that at any moment I can cast off

the lines and sail anywhere in the world. It’s freedom. It’s pride of

ownership. It’s a perpetual challenge. And for a retired person, now in the

third act of my life, the physical demands force me to stay in shape while the

mental requisites keep the dementia dogs at bay.

It’s raining outside as sit here in my

boat. She rocks gently with the incoming tidal surge. I have a small space

heater going, coffee is brewing, and there is soft music playing over the boat’s

sound system. Another boat leaves the marina and its wake laps up against the

stern. Earlier, a Great Blue Heron was perched on my bow pulpit. Moments ago a

Pelican dove into the fairway just a few yards away. Since we are sailing in

the morning, I just may cook dinner on the boat and spend the night.

I’ve heard all the jokes about boat ownership. These

come from friends who have hard hearts and little romance coursing through

their veins. In response to the tired question, “What are the two best days in

a boat owner’s life?” My answer is, “the last day I sailed my boat and the next

day I plan to sail it.”

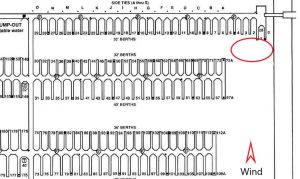

August can be an interesting time at the Tradewinds docks. Lots of wind, accompanied by the normal “too much wind docking entertainment.” One particular August Saturday saw the day end with two boats “parked” at the exact same spot, laying across the dock fingers of multiple slips (Windfall, Megalina, and Seabreeze). Fortunately, not at the same time. About 15 minutes apart. Also fortunately, without any damage to anything.

August can be an interesting time at the Tradewinds docks. Lots of wind, accompanied by the normal “too much wind docking entertainment.” One particular August Saturday saw the day end with two boats “parked” at the exact same spot, laying across the dock fingers of multiple slips (Windfall, Megalina, and Seabreeze). Fortunately, not at the same time. About 15 minutes apart. Also fortunately, without any damage to anything.