The following is an excerpt from my book, “The Captain And Mr. Shrode,” and was written in the harbor of Huatulco in southern Mexico, on the last leg of our circumnavigation.

When one undertakes a venture such as ours, he perhaps holds out the hope that the experience may toughen him a bit, make more of a man of him, that sort of thing. He’ll walk with a salty swagger and have a certain air that sets him apart from the ordinary man. The last thing one wishes is to be proven a weakling, a fool, a coward.

But Daniel Patrick Moynihan once said that if you live life fully, it will break your heart, probably quoting an old Irish proverb. Similarly, it seems that if you sail enough miles, the sea will turn you into a poltroon. Just what you didn’t want.

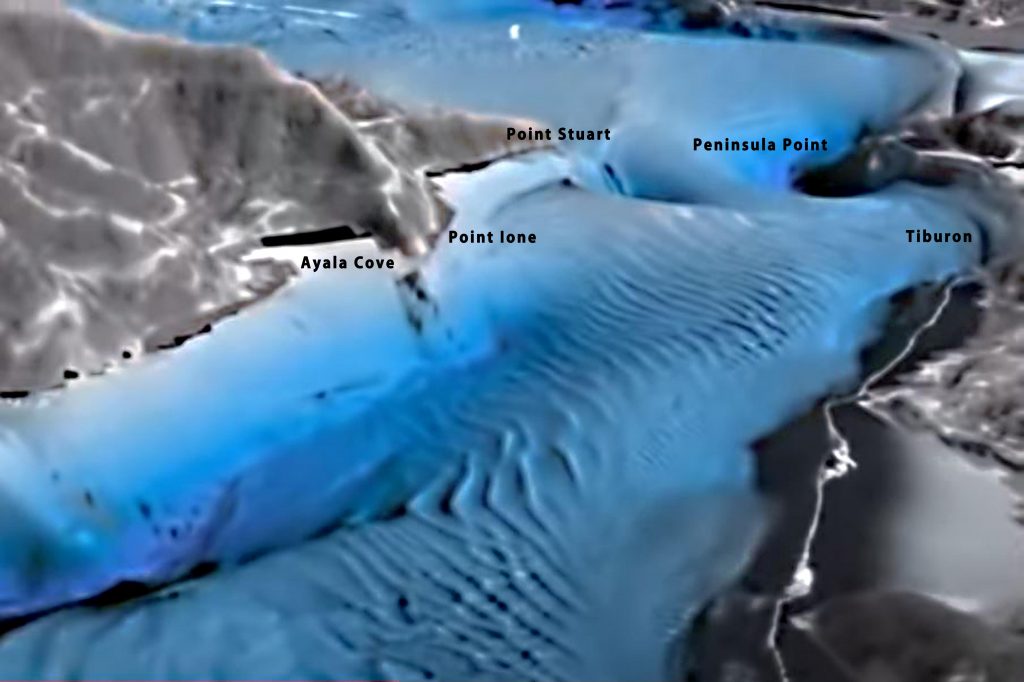

The crew of Maverick arrives at Huatulco where all the books say it’s safe to wait out a Tehuantepecer. The Captain looks at the bay, which is not too deep, and the faxes, which predict 12-foot waves gliding oh-so-gently by only a short distance away. He recalls that waves have the property of refracting around things. Looking at the headland that protects the bay, he hypothesizes thusly: Here lies the sort of thingamajig around which a wave, if it got a notion to, might refract, sending its mischievous energy into the harbor. The books say no, it’s safe. Never one to be comforted by facts or evidence, the Captain has developed that particular talent of the coward: to be afraid.

Seeking reassurance, he asks the port captain if the harbor is safe, if the mean old waves might refract into the harbor. The port captain pats his hand and looks meaningfully into his eyes, having seen his sort before. “No, it is very safe here.”

Then the Captain goes to see the manager of the marina, Andrico, who has the sort of sporty name that tennis pros and ski instructors favor, and asks him the same thing. “No, not to worry,” he says in his best bedside manner, as if reassuring a little old lady.

So the books, and the Port Captain, and Andrico, and the fishermen, and the indulging looks on the faces of all who are brave, say that the nasty waves will not refract around the headland.

But the waves refract around the headland.

On Sunday, when the Tehuantepecer is scheduled to start blowing to 50 knots, the right side of the bay, the one the locals said was safest, starts to look untenable and will be if it gets worse. We move to the other side of the bay and as usual make certain we’ve got the hook well stuck. Later, the other cruising boat in the anchorage follows.

On Monday, the winds gusted to 65 knots, hurricane strength, out in the Gulf, and we had gusts of up to 40 in the bay. Every vessel in the bay dragged its anchor, except Maverick. Okay, there were only three other vessels. But one was a 60-foot steel trawler, and another was a large barge. Both craft were anchored by professionals—members in good standing of the “nothing to worry about in this snug harbor” school of thought. The trawler crew was aboard and tried to re-anchor but couldn’t and eventually settled for tying up to the pier, which, with the surge, was a very ugly solution. The barge fetched up on the rocks. The cruisers were away in town, so when we saw their boat was dragging in the strong wind and chop, we got into the dinghy with three fenders and clambered aboard to try to keep the fenders between their boat and a huge channel buoy. As the boat dragged past it, we found some lines and tied two to the buoy to stabilize the situation until the weather died down. This bit of maneuvering with the dinghy, boat, lines, and buoy in the midst of a chaotic scene could not be described as elegant. The cruisers were not ungrateful; the boat would have foundered.

An exasperating fact is that most of the time, the dashing, devil-may-care skipper who throws out 30 feet of rode in 20 feet of water and says, “Who’s ready for a brewski?” is going to be fine, while the silly crew of Maverick that spent FIVE HOURS before they were satisfied that their anchor was well set in Mykonos will look like fools. Most of the time even a poorly set anchor will not drag, the boat will not be broken into, the through-hulls will not fail, we will not lose our passports, the lighthouse will be working, the rig will not come down, the hull will not come apart, the navigation will be obvious, the chart will be correct, the oil cooler will not spring a leak, lightning will not strike, the boat will not swing onto the reef in a gale, and all your worries will seem the far-fetched scenarios of a guy with no self-confidence and no sense of adventure.

When we were in Lipari, I saw an excursion boat loading passengers for a day trip. Everyone was in a festive mood, the crew welcoming the visitors, handing out drinks, helping them stow their bags. Only one man stood apart from the rest, leaning on the rail with a worried look on his face, staring down at the mooring lines. Though he wore no uniform, I knew in an instant he was the captain.

It’s a little humiliating to feel the need, or even the duty, to be a fussy worrywart. It’s really not what you had in mind when you visualized yourself as Captain. There is no dignity in paranoia, when the movies teach us that the hero is like Butch Cassidy or the Sundance Kid, jumping off a big cliff and not getting hurt. On the other hand, in the book, Little Big Man, there is a story about Wild Bill Hickok that I assume is apocryphal, but nonetheless like many apocryphal tales it is a good one. As he approaches a bar to get a drink, a man at a bar stool on the end who seems to be passed out drunk lifts up his head and raises a gun to kill him. Hickok, prepared for that eventuality because he’s paranoid, has his gun hidden behind the hat he holds in his hand, and blows him away. Little Big Man is amazed, and asks Hickok how he knew that guy had a gun, and Hickok replies that it was just a hunch, and when he gets hunches like that 99 out of 100 times he’s wrong. “But it’s that one time in a hundred that pays me for my troubles.”