Inland Navigation Rules

Nav Rules Make Easy

Rules 7 – 8 – 9 – 10

In the Nav Rules Made Easy series, we’ll explain each Inland Navigation Rule, with an emphasis on the information that’s most important for recreational sailing in the San Francisco Bay. We won’t include portions of the rules that are highly technical and intended for commercial mariners.

Note: If you travel more than one mile outside the Golden Gate Bridge or if you charter a boat in another country, the International Rules apply. Many of the International Rules are exactly the same as the Inland Rules. However, there are also a few that contain important and significant differences from Inland. Make sure that you study and learn International Rules if you are traveling in international waters.

Rule 7 – Risk of collision

Rule #7 tells us to avoid any possibility of hitting another boat or obstacle.

Maintain awareness of your surroundings. Make sure that you can see 360 degrees around your boat.

Use all the tools and equipment available to help you be fully aware of other boats and objects on the water.

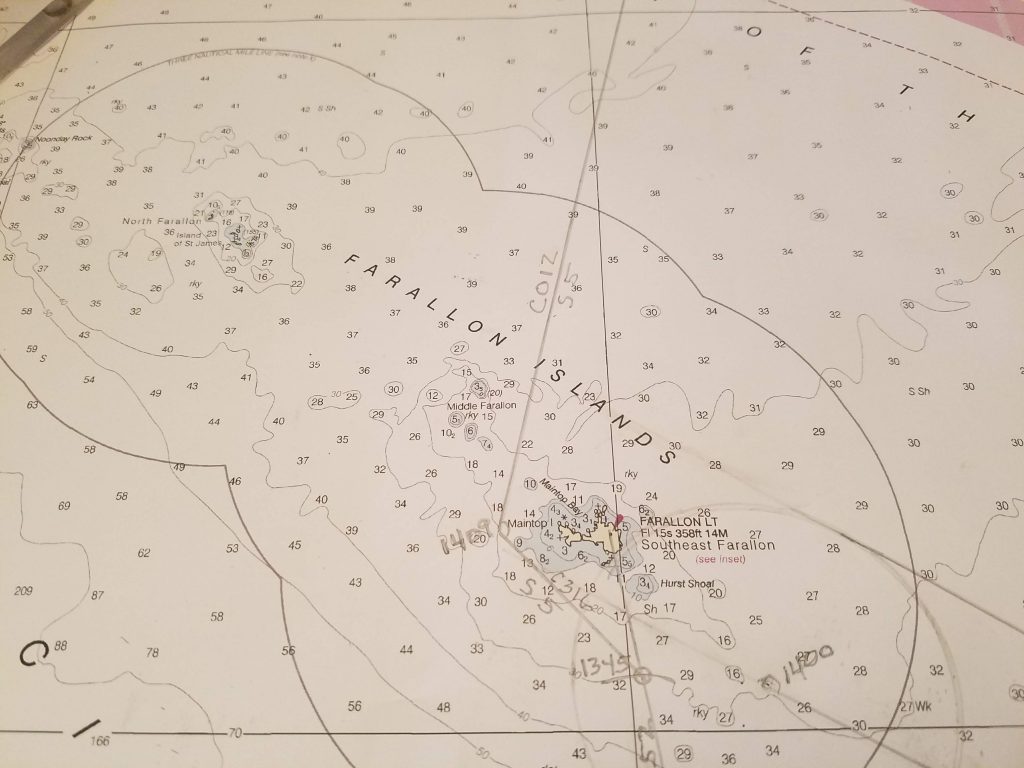

Use binoculars, sunglasses, radar, boat tracking software applications, chart plotters and nautical charts to help you see other boats.

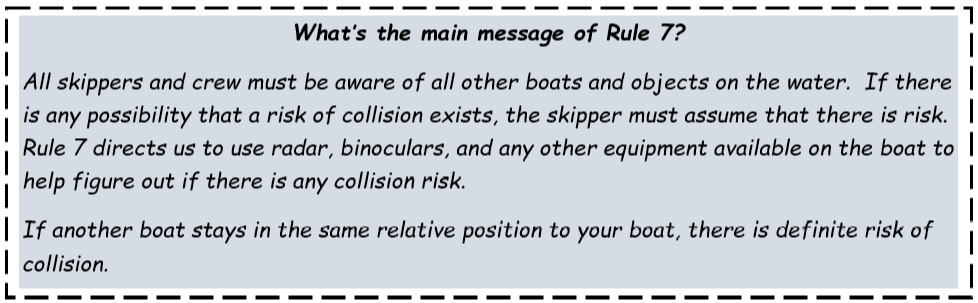

Be aware of other boats on the water and decide if there is any risk of collision. If you think there is any possible risk of collision, assume that there is risk and then take appropriate action.

Let’s consider a few examples.

What if the lookout sees an image on radar that is not clear and wonders if the image could be another vessel or object on the water? In this case, the rules tell the lookout to assume that the image is another vessel or object, and to avoid that area.

What if you’re out on the water and there is a lot of sun glare making it hard to see? Make sure that you have sunglasses that block sun glare so you can see other boats. If you see something and you’re not sure if it’s another boat, Rule 7 tells you to assume that it is a boat.

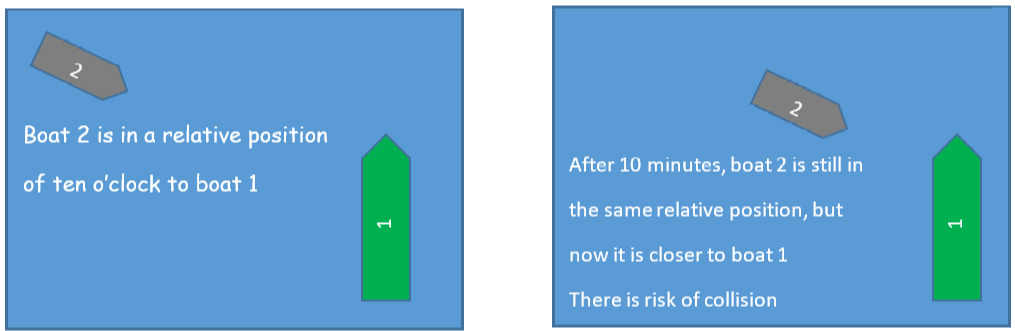

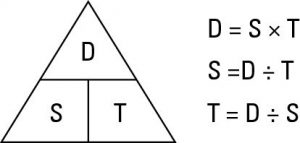

Rule 7 also talks about the concept of “constant bearing, decreasing range.” This means that another boat stays in the same relative position to your boat as the boats become closer to each other. If the position stays the same as the boats get closer, there is definite collision risk.

What if you see another boat on the water and the boat’s position stays the same relative to your boat? Let’s say you see a boat coming from your starboard side at ten o’clock. Ten minutes later, the boat is still at ten o’clock relative to your boat. Since the other boat’s position did not change, your boat and the other boat are on a collision course.

There are some situations when the other boat’s relative position will actually change and yet you are still on a collision course. This can happen if the other boat is very large, like a barge. It can also happen if the other boat is very close to your boat.

Rule 8 – Action to avoid collision

When your boat is the “give-way” vessel, you are required to change course or speed to avoid a collision.

Make course changes obvious enough so the other vessel can clearly see that you are altering course to avoid them, and soon enough to avoid the other boat’s skipper getting nervous.

There are some standard, recommended course changes to make when you are the “give-way” vessel:

- If you are under power and avoiding another power boat in a crossing situation, steer toward the stern of the other boat

- If you are under power going toward another power boat head-on, steer to starboard and pass the other boat on your port side

- If you are sailing on port tack and the other boat is sailing starboard tack, steer toward the other boat’s stern

- If you are sailing on the same tack as the other boat and you are upwind (the windward vessel), steer toward the stern of the other boat

The key point in this rule is to make a big enough course change so that it is obvious to the other boat. Make course change sooner, rather than later. Make the change before the other skipper gets nervous.

When you change course to avoid collision, keep a safe distance from the other boat. Don’t go too close!

After making your course change, wait until the other vessel is far enough away that there is no possible risk of collision. Once you are fully clear of the other boat, resume the course you were on before your course change. Sometimes, the situation requires you to reduce speed rather than make a course change. This can happen in close-quarters situations. Do all you can to make a significant reduction in speed, even if it means using reverse to help slow your boat.

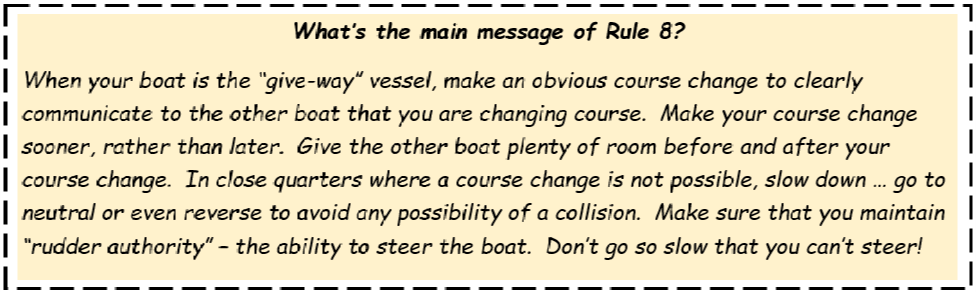

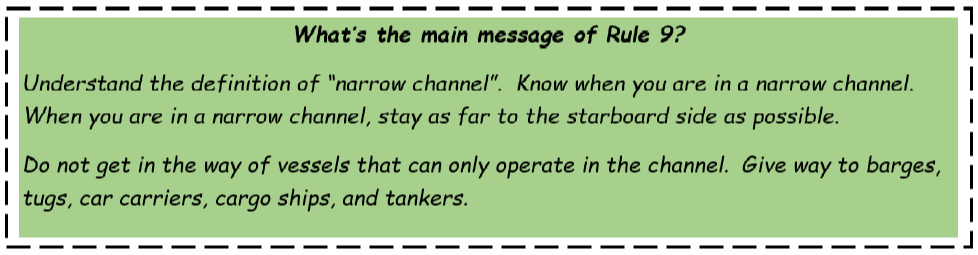

Rule 9 – Narrow channels

First of all, what’s a “narrow channel”? The term “narrow channel” is defined by the vessels in the channel. You are in a “narrow channel” if there are any vessels that are restricted to staying within the channel because of depth or obstructions.

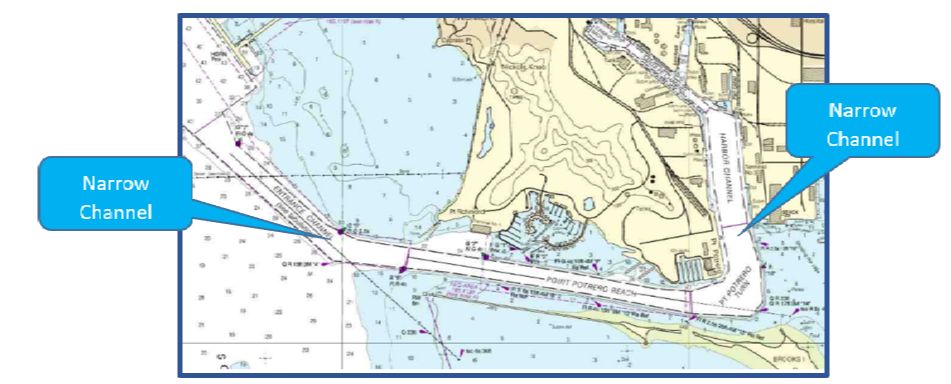

A good example is Potrero Reach. As you know, the large commercial barges, tugs, and tankers must stay within the channel or risk going aground. So, Potrero Reach is a “narrow channel” It continues to be a “narrow channel” all the way under the Richmond/San Rafael Bridge and into San Pablo Bay. When you sail in the Potrero Reach shipping channel, you are in a “narrow channel”.

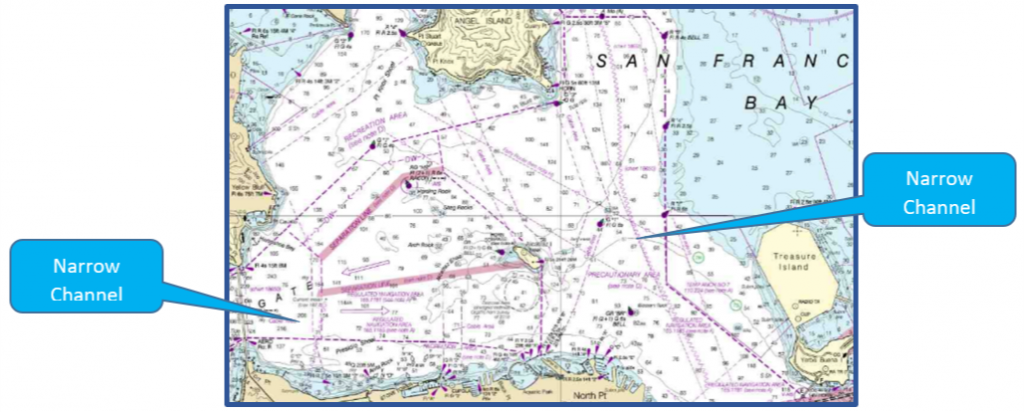

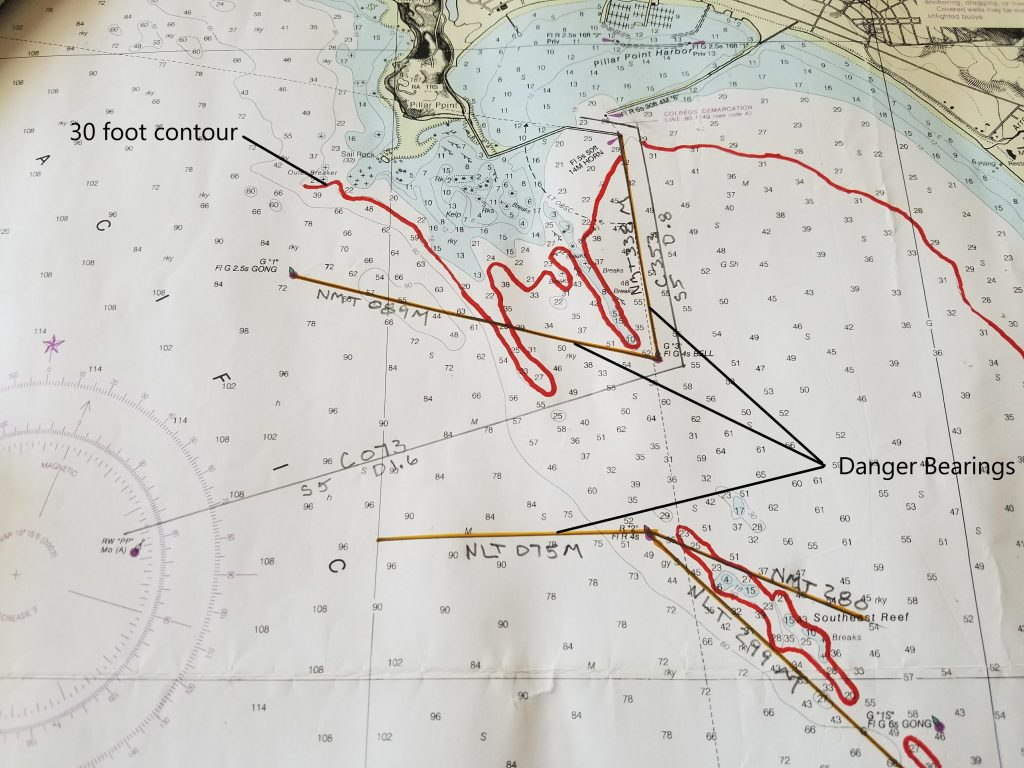

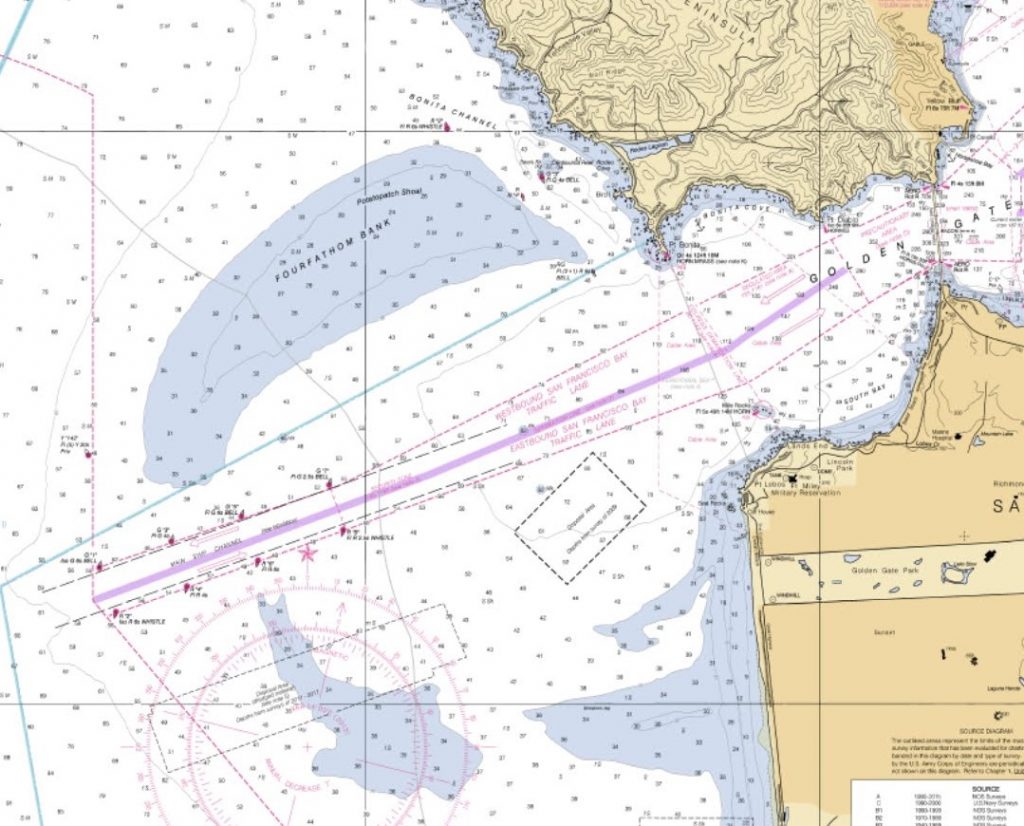

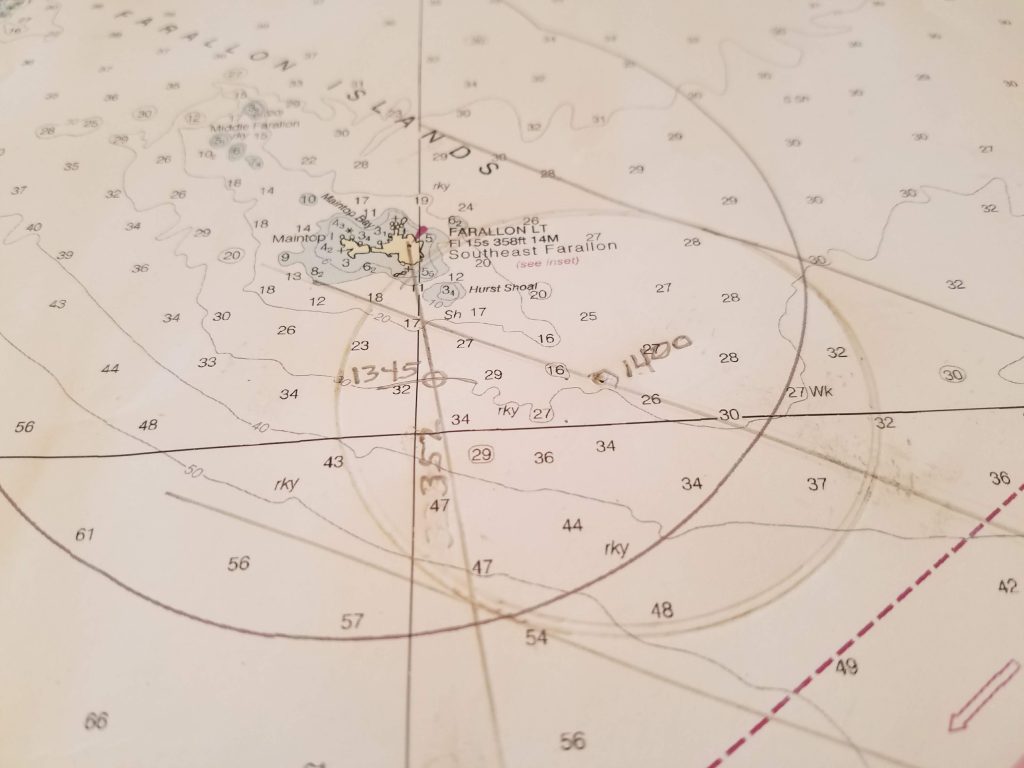

Now that you know the definition of “narrow channel”, look at the chart of San Francisco Bay. Look at all of the shipping channels!

When you are in a “narrow channel”, there are specific rules that apply:

- Stay as far to the starboard side of the channel as possible.

- Do not get in the way of vessels that can only operate in the narrow channel. Stay out of the way of tankers, car carriers, container ships, tugs, and barges.

- Do not cross the channel if your boat will get in the way of boats restricted to the channel.

- Do not anchor in the channel.

- If you come to a blind corner in the channel, use a sound signal of one prolonged blast before going around the corner. One prolonged blast is a horn sound for 4-6 seconds.

- If you are overtaking another vessel, remember that you are the “give-way” boat, even if you are under sail! The vessel being overtaken is the “stand-on” boat. Stay out of their way.

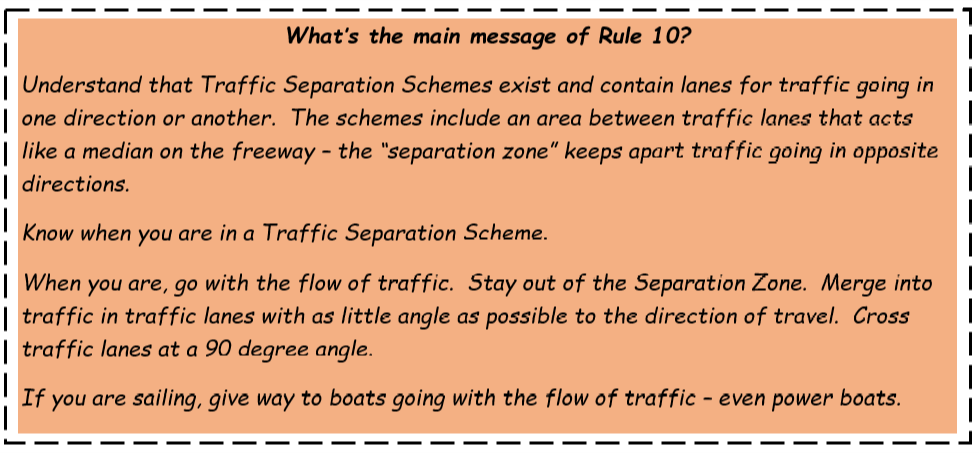

Rule 10 – Traffic separation schemes

In the busiest commercial shipping areas, there are designated traffic systems, called schemes. Within traffic schemes, there are lanes designated for traffic to flow in one direction or another. Generally, there are eastbound and westbound lanes or northbound and southbound lanes. It’s just like the way a freeway is designed. One lane goes one way and the opposite lane goes the opposite way. In between the two lanes, there is a “separation zone” which is just like the median on a freeway. The separation zone keeps ships going in opposite directions apart.

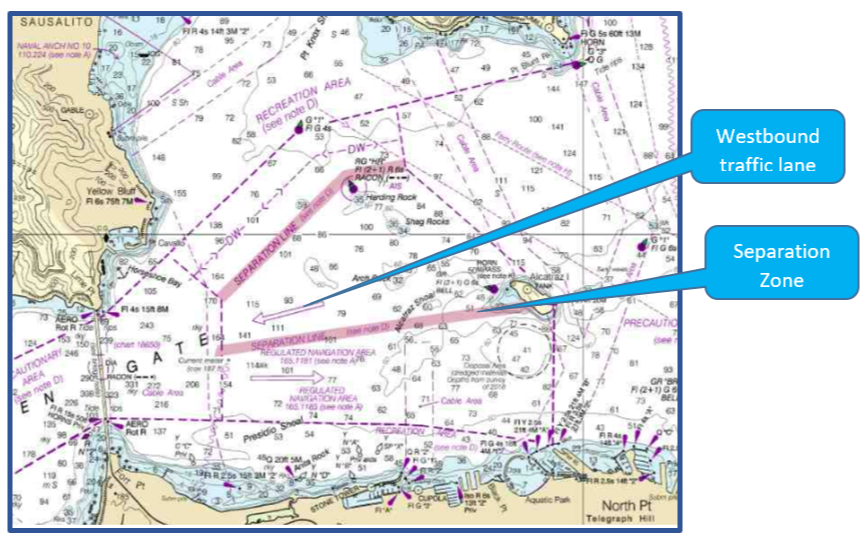

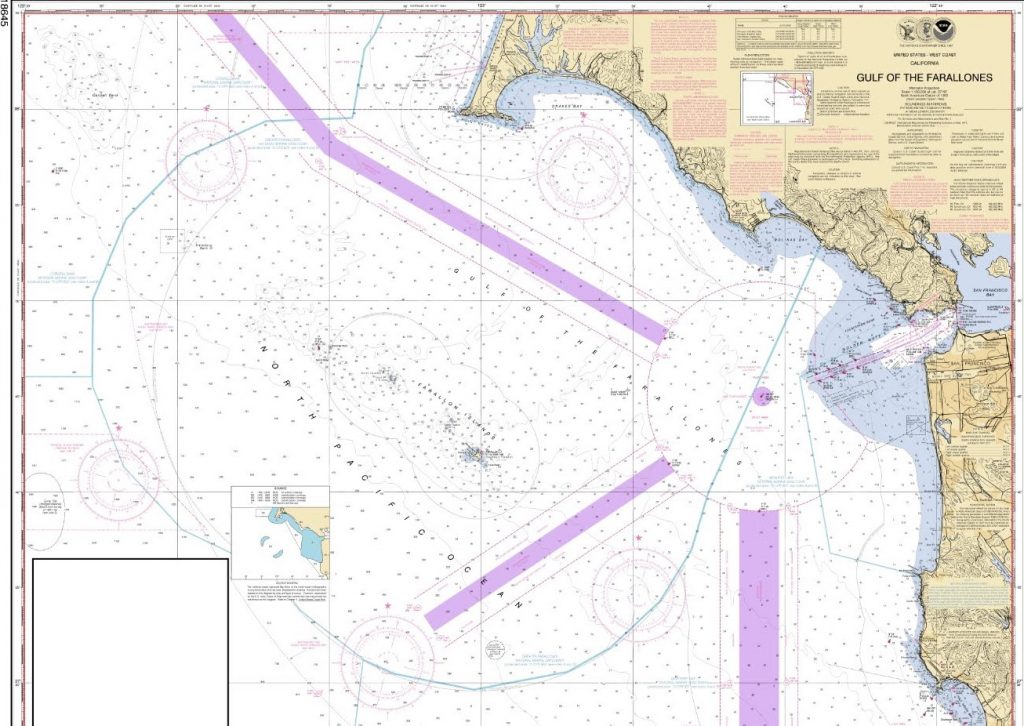

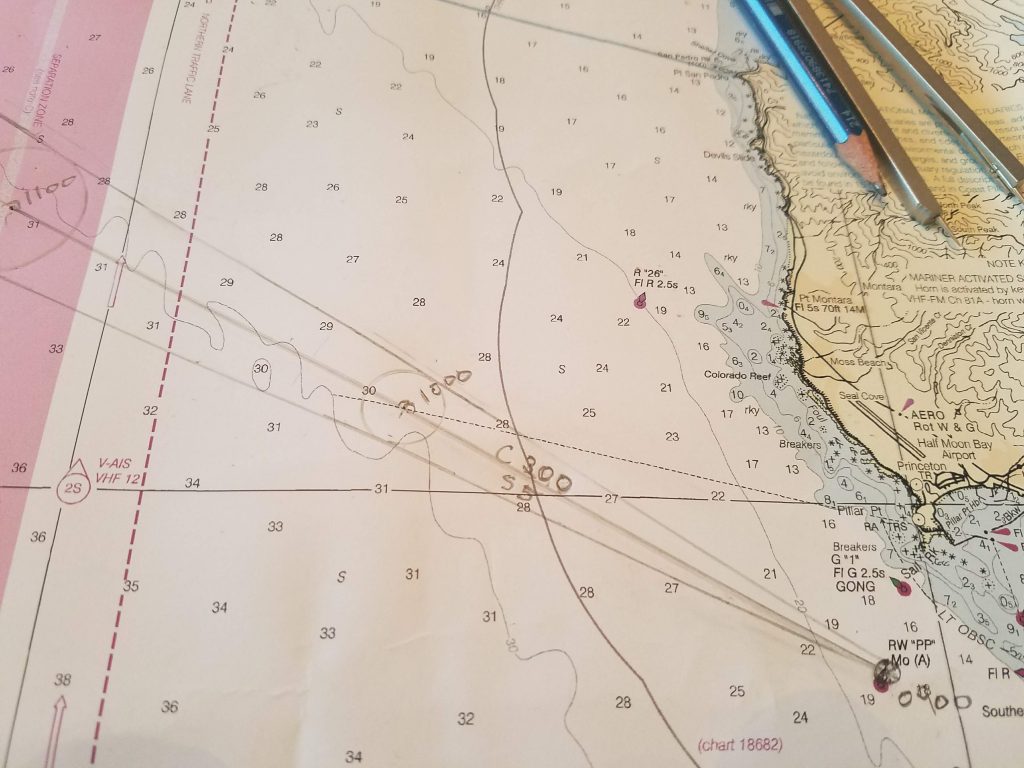

Look at the nautical chart and note the arrows in the shipping lanes. The arrows show you the traffic flow. Find the wide magenta-colored lines. These are the separation zones at the entrance to San Francisco Bay.

There are specific rules about boat traffic in separation schemes:

- Use the traffic lane that is designed for the direction you want to travel. Use the eastbound lane when you are traveling east and the westbound lane when you are traveling west.

- Stay out of the separation zone unless there is an emergency and you have to use the separation zone to avoid danger.

- You can use the separation zone to fish.

- When merging into a traffic lane, merge with as little angle to the lane as possible. This is similar to getting on a freeway using the onramp.

- Avoid crossing traffic lanes. If you have to cross traffic lanes, cross at a 90 degree angle to the lane and the traffic flow

- Do not anchor in any traffic lanes or in the separation zone

- Be extremely careful when you are in the area at the end of a traffic scheme.

- If you are not using the traffic scheme, avoid the area. If you are not using the traffic lanes, stay clear of the area.

- If you are fishing, you must give way to all other boats.

- If you are sailing, you must give way to all boats who are in the traffic lanes going with the flow of traffic – that includes power boats.